Lee-Anne Poole

From the very first lines in Lee-Anne Poole’s play Talk Sexxxy, playing at the Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery just until this evening (January 19th, 2025), she is stressing the artifice of the event that we, the audience, are waiting to witness. “This is a play,” she says, clearly. “This is a play I wrote. I am performing this play.” She tells us that aspects of the play are drawn from her memories of real events that happened fifteen years ago, and that some aspect of the play are fictional. The line between the real and the imagined is never specified. Poole notes also that she is a playwright; she is not an actor, but she is also “not not an actor,” which is apparent throughout the very charming and emotionally compelling performance that she gives in this piece.

The story of Talk Sexxxy, at its core, really seems to me to be a story about isolation and about loneliness. Our protagonist, Kristie, has just had a heartbreaking breakup and they have isolated themselves in their apartment. They are actively avoiding their friends. They are at least attempting to lie to the people who care about them in attempt to keep their worries at bay long enough to be left alone. And once alone they start working as a phone sex operator. The men who are calling also suggest a profound level of isolation and loneliness. Some stay on the line for hours, seeming just to want someone else to be on the line with them- to listen- to talk to them. To be there with them in their own empty space.

Although someone who considers themself to be sex-positive, Kristie is young, and in some ways naïve about what these men might want to talk about during these phone calls. Naïve about what it means when the company she works for has a policy that nothing is considered taboo. For some people their own sexual desires are the very thing that isolate them from mainstream society. What are the ethics around trying to empathize to some degree with these people? What are the lasting implications from being paid to be in such proximity to fantasies that many would say cross a line: a moral one and, perhaps, also a legal one?

The play is darkly funny, in Poole’s characteristically self-deprecating way, but in a way that I think mirrors Kristie’s experience- it sort of crashes into its own darkness suddenly. Suddenly Kristie is in over their head, and, in a way, so are we. What do you do when you are in over your head and you have pushed everyone who cares about you away? What happens when you have tried to convince everyone, even yourself, especially yourself, that you are totally fine and okay, no worries, and then suddenly you have to admit that’s bullshit? While Kristie’s story about being a sex worker is, obviously, very specific, I think this aspect of her situation is wildly relatable for folks and that many of us have been both Kristie and her friends at different times in our lives.

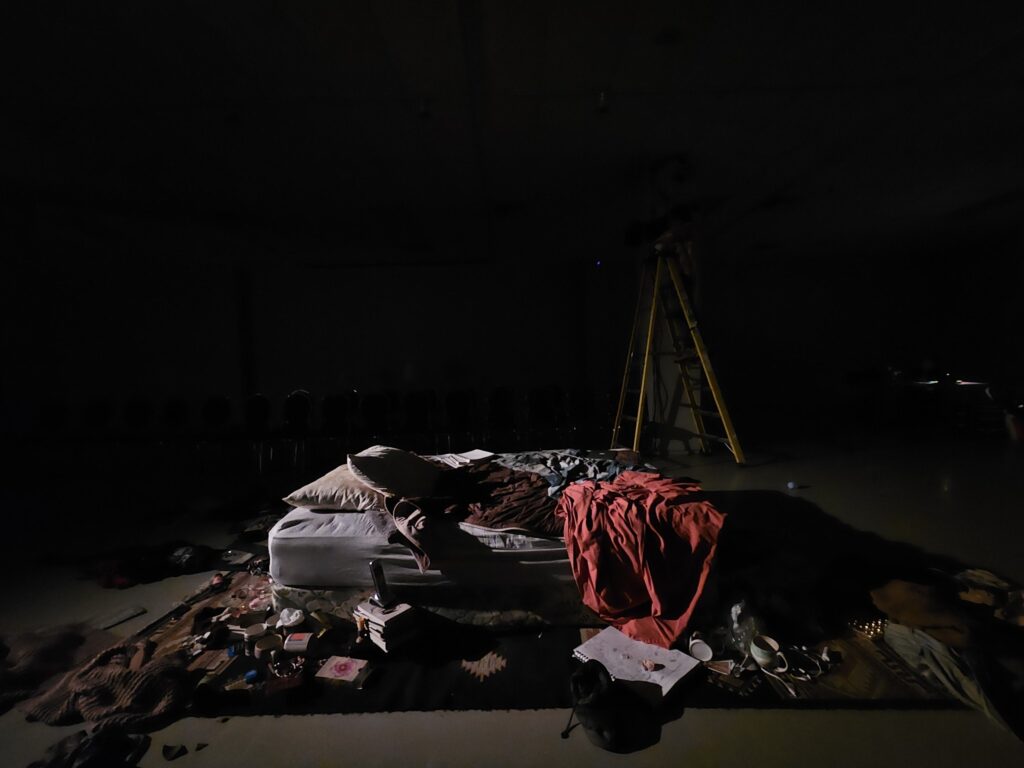

The audience sits around a bed surrounded by an absolute mess of clothing and garbage and other items you might find in a bedroom, which also tells the story, I think, of someone who is going through something difficult and may be isolating from the rest of the world. I had assumed Poole would spend most of the play sitting on the bed, but she doesn’t. Director Stephanie MacDonad has her largely moving around the bed- and Kristie is narrating a story that has already happened, she is not acting it out in a present tense, so the bed exists almost like a ghost from another time: as though a younger version of Kristie is on that bed, we just cannot physically see her. The set from the 2014 production is also in an adjacent room, fully set up. We can watch a silent archival of that production on a television screen when we enter or exit the space. 2014 Stephanie MacDonald is very much here too. MacDonald’s choice to have Poole standing so much addressing us directly also plays into that line between how much of this is real and how much of this is fiction. How much of Kristie is Lee-Anne and how much of Lee-Anne is Kristie? How much of this is acting and how much of this is being? We see this in Leigh Ann Vardy’s lighting design as well, how nuanced the difference in the lighting is that signals which part is not a play, and then which part is a play. This mirrors, of course, the phone sex, where Kristie plays the character of Jennifer (or a plethora of other characters, depending on where she falls on a complex spreadsheet), and how many men believe that Jennifer is real, and that everything she says is true, and that their relationship with one another is genuine? Some, for sure, know that it is artifice, but Kristie can’t help it, sometimes aspects that are real bleed through.

In both cases, this play and in the phone calls, does it ultimately matter whether we know what is objectively the truth and what is part of a story? The idea of policing people’s thoughts, their fantasies, their stories, if they are truly and completely divorced from real-life action, is morally murky territory that I think many people feel uncomfortable even wading into even a little bit. I feel uncomfortable wading into it even a little bit. A fantasy is also both real and not real, in a way. It can be vivid and detailed and evoke real emotions, but it still exists in someone’s own imagination. A play, like a fantasy shared out loud by two people, is a real experience, a tangible memory, but still, largely a collective suspension of disbelief: like communal dreaming.

Talk Sexxy is a play about something that actually happened shaped by a playwright into something that could have happened, and then shaped by a playwright, a ‘not not an actor’, and a director, into something that is also about how a play is conceived, and executed, and given to an audience to process in their own way. Laughter is appreciated. And Poole is, I believe, genuinely, truthfully, happy to have you with her on this journey and in this physical space.

Talk Sexxxy closes tonight, January 19th, 2025, at the Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery (5907 Gorsebrook Avenue, Halifax) at 7:30pm. The show is sold out but you can join the Wait List here, if you wish. Tickets are on a sliding scale between $10.00 and $40.00.

The Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery is wheelchair accessible. More accessibility information/options will be emailed to all ticket holders before the show. The full script of the play is included in the show’s programme.

1 thought on “Talk Sexxxy: This is a Review. This is a Review I Wrote Last Night Upon Seeing This Play”

Comments are closed.