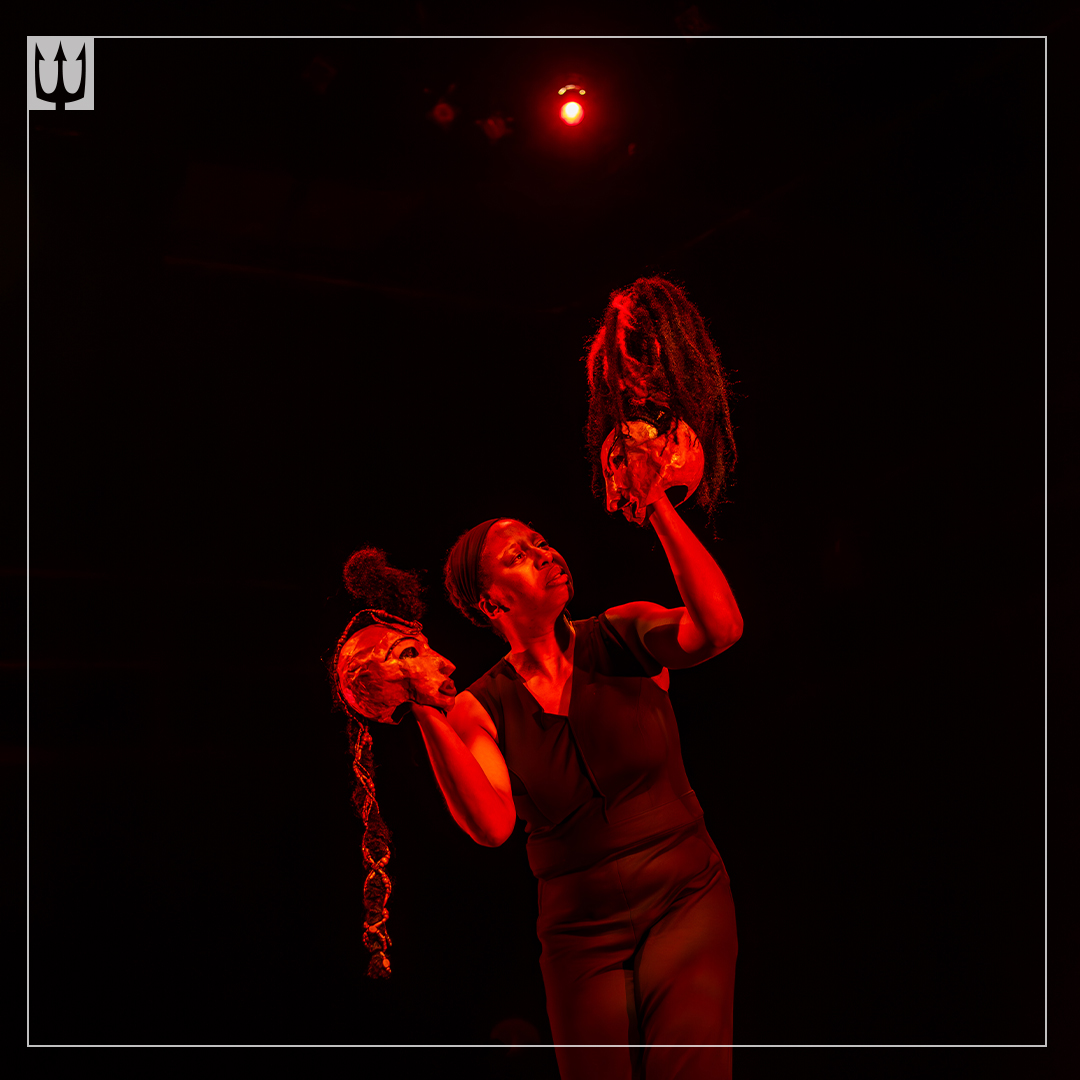

Raven Dauda Photo by Stoo Metz

When Raven Dauda was ten years old she got bitten by the theatre bug while playing one of the Evil Stepsisters in an elementary school production of Cinderella. Although initially disappointed to not be cast in the lead role, little Raven got a huge laugh when she improved one of the actions to her song in the moment onstage, and she was immediately hooked. Before we sat down together to chat about her one person show, Addicted, which plays at Neptune Theatre’s Scotiabank Studio Theatre until March 24th, 2024 I watched Dauda perform a short selection of scenes from the play, and it was clear just from these snippets that this is absolutely a whirlwind tour de force performance and a must-see. Go get your tickets now and then come back to read the interview.

She grew up as a latchkey kid putting on plays with the neighbourhood children, and as a teenager she performed in school plays and in the Sears Drama Festival, which at that time was adjudicated by R.H. Thompson. “I got a Best Actress Award from R.H. Thompson,” she says, “and that launched me. That really set me on this path.” She had an unfortunately all too familiar experience being torn down at theatre school- having one of her instructors at Studio 58 in Vancouver tell her that she was a bad actor. “I just wasn’t strong enough to stand up to that. You’re just like, ‘oh, they know what’s best. They’re the teachers. They’re the experts, so I must suck… Obviously not.” Eventually she was able to return to Vancouver victorious, playing Christine in Miss Julie: Freedom Summer at the Playhouse, a role for which she won a Dora Award in Toronto when the play was produced there by Canadian Stage.

Throughout many of her years as an actor Dauda also worked as a server at a restaurant in Toronto, Joso’s, in the upscale Yorkville neighbourhood, just up from the Four Seasons Hotel, so it was not uncommon for Dauda to be serving celebrities, or staying at the restaurant late for special after-hour parties. She began her shift with a shot, and would often be invited to have some drinks during these parties, and that became part of a cycle of drinking. She was not the only member of her family to struggle with addition. Her father had really suffered with alcoholism, and she sees all her siblings experiencing the impacts of that in different ways.

Addicted came out of d’bi young anitafrika’s Watah Theatre in Toronto while Dauda, now sober, was an artist in residence there. Each semester the artists in residency would create a fifteen minute piece based on the work they were doing, so at the end of the year Dauda had a forty-five minute show. One of her High School drama teachers came to the play’s first workshop and was so excited by the play he insisted that it needed to be produced, and that’s how Addicted first took off. Initially Dauda says that the play was really an exercise to stretch herself as an actor, she plays multiple characters with an impressive array of different accents, including one character with an accent based on restauranteur Yoso. “I chose characters and accents that I would never be cast as,” she says, laughing, “and at the same time it was therapeutic. Everything in the show is from a form of therapy that I have learned along the way, from the courses that I’ve done and the groups that I’ve been a part of. So it was really just a project to help me.” She draws not only on her own experience, but she is very interested in the intergenerational aspects of addiction. “I warned my family too,” she says, stressing that the characters have evolved and changed to protect their privacy, “but one of my sisters did say when she saw the show, ‘I’m going to be very careful what I say around you.’ She laughs.

“I’m so thankful because I realized how [addiction] is bigger than me, and I love how theatre helps to heal- yes, it’s for entertainment, and it’s absolutely a way for us to escape, but it can also be a way to look on ourselves and reflect. I’m so proud of this show. I just hope that people really enjoy it.”

The play also has a lot of comedy and Dauda uses puppetry as part of her storytelling. “The puppets are a therapeutic method too because it’s removing it from yourself. It’s a bit easier to digest. She laughs referencing one of her Ancestor characters, Nichua, whose story of systemic trauma and abuse is told through puppetry. “It’s a bit easier to take when it’s puppets,” she says laughing. “We need humour, and it’s also how I deal with things. That’s how I’ve always dealt with things. It’s so funny because earlier on in my drinking it was an automatic default in a way that wasn’t always helpful. I would just make jokes about things like, ‘oh- haha- nope, it doesn’t bother me.” I would do that distraction, and we see that in the beginning of the play, (protagonist) Penelope does this JOKE TIME to avoid the voices going on in her head. It’s funny because now I’m using the humour in a healthy way for healing. So, it’s not that joking is bad, it’s now that I’m joking in a way that is helpful, that is a soothing balm to help the medicine go down.

She also chose the characters in the rehab facility specifically as people who were as far away from her own self as possible. “The characters are aspects of myself and I gave them things to say that, at the time, I wasn’t comfortable with saying. Especially Vance, he’s a bit of a really rough guy, he’s like a Scarborough Italian type of guy, and his lines have changed quite a bit, but in the beginning he was not likeable. He was just an ornery guy, but I loved his frankness, because I couldn’t do that. Granny is an amalgamation of my mum and my aunt,” she slips seamlessly into a Jamaican accent, “so they’re always quoting Jesus and the bible,” she returns to her own accent, “they have these Jamaican sayings- I make fun of them in the play, but there’s some Jamaican sayings that make no sense. So Granny says, ‘Don’t ask me what dat means…Yuh know what it means’ and we’re like, ‘not really, but okay.’ She laughs.

Conversely, she also plays Jessie, a young Irish kid, “I was trying to challenge myself and choose something that was the furthest removed from who I am,” she laughs again, “and then he sort of ended up being this fun like good, loveable kid who is really trying.” Jessie got addicted to oxycontin after a sports injury. “He represents purity, curiosity, and support. He really represents having support in the world,” she says. It’s important, Dauda stresses to understand that while some addictions have more stigma than others, the way they work biologically and chemically are often the same or similar. The dopamine kick we get from our phones is the same that we might get from a drug. The body also processes sugar the same way that it processes alcohol. “Everybody’s got something, everybody needs something,” Dauda says, “and at the end of the day, it’s actually not about what the thing IS, it’s about what’s behind it, and why we feel the need to go outside of ourselves. What are we running away from?”

The Ancestors’ story takes place in Sierra Leone, as Dauda’s father was Sierra Leonian. However, she also had a Nigerian Prince character, and subsequently found out through 23andMe that she is part Nigerian as well. “Isn’t that crazy?!” she says with a huge laugh, “ I’m a very spiritual person, so I do feel like my ancestors are whispering in my ear because sometimes I don’t consciously know where these characters are coming from.” The Ancestors represent a curse in Penelope’s family, which alludes to the way intergenerational trauma and addiction are often connected. “I wanted to look a bit at Epigenetics. They’ve done this test on mice where it shows that they will react from a trauma generations before them. I firmly believe that we carry so much in our DNA and we’re just reactive. In my process of healing I had to learn how to love myself and give myself a break, as I villainized myself so much [always being like] “Get it together, Raven! Be like Beyoncé!” We tell ourselves these stories and compare [ourselves to others], and I wanted to do what I could do to release the generational trauma aspect, to acknowledge that it’s in our family. I’ve learned just from intention, just by putting an intent on something- because the only way out is through- you gotta actually feel the thing first before you can let it go. I can’t just drink it away. You actually have to sit with the shit and the pain.” I venture that that is why we don’t want to do it, because it’s so hard, and she agrees, laughing. “But the generational trauma aspect just helped me to give myself a break, that it’s not all on me.”

Addicted was written to be the first part of a trilogy, and the next play will focus entirely on generational trauma, skipping around in time and geography, following different members of Penelope’s family, and seeing the ways they are coping with the same familial issues and persistent cycles. “I don’t think it’s something that’s really been explored,” she says, “I really want to look at how we treat each other, the biases that we inherit, and how we move from there. What’s that about? A child isn’t born racist, it’s what’s handed down to them. Hurt people hurt people. I want to get into that chestnut and build more puppets to [tell those stories too].”

At the heart of the play is a lesson that Dauda learned from Vipassana Meditation, a ten day retreat where folks meditate in silence, which is what helped her initially get over her first withdrawal, “If you ever feel like you don’t have the answer, just take a moment and just breathe. It will come [to you]. It feels like [it won’t], and we freak out and start doing things, but that’s the thing about addiction, you just go moment to moment. You just breathe. It will pass. You’re okay.”

Addicted plays at Neptune Theatre’s Scotiabank Studio Stage (1589 Argyle Street, Halifax) until March 24th, 2024. Tickets are $23.00-$40.00 (based on seating) and are available ONLINE HERE, by calling the Box Office at 902.429.7070 or in person at the Box Office at 1589 Argyle Street. Performances are at 7:30pm Tuesday to Saturday at 2:00pm on Saturday and Sunday.

Please be aware the Addicted deals with issues of abuse. Characters display symptoms of trauma, substance abuse and addiction.

This show is approximately 1 hour & 45 minutes long (including an intermission).

Babes in arms & children under 4 are not permitted in the theatre.

Neptune Theatre is fully accessible for wheelchair users. For more Accessibility Information Click Here.

World Theatre Day: My God Is It Ever The Time to Invest in Canadian Plays

World Theatre Day: My God Is It Ever The Time to Invest in Canadian Plays