On Monday evening it was my supreme pleasure to sit in a very crowded Princess of Wales Theatre to listen to the man who has been undoubtedly the single greatest inspiration to me in all my artistic endeavours, the hero who has shaped, enriched and informed my understanding of musical theatre and of the creation process and music’s ability to reach the most intimate corners of the human soul, the incomparable Mr. Stephen Sondheim. Des McAnuff, who introduced the evening, called him “the single most creative force in musical theatre of our time,” and I would agree. There is no single living artist who has made such experimental and historical breakthroughs in the construction of musical theatre, changing the world’s definition of this type of theatre and its concept of what a musical *could* do and could be. From Anyone Can Whistle (1964) to Company (1970), Sunday in the Park with George (1984) and The Frogs (2004), Sondheim’s work has continually been innovative, complex, dynamic and beautifully poignant elevating musical theatre to a sophisticated theatrical plane equivalent to the most lauded straight plays of the contemporary theatre cannon.

The Evening With Stephen Sondheim in Conversation was moderated by Robert Cushman, who Des McAnuff introduced as “one of the finest minds in Canadian theatre.” Cushman is the theatre critic for the National Post and an eight time winner of the Nathan Cohen Award for excellence in theatre criticism. The following is an approximate transcript of the conversation between Mr. Cushman and Mr. Sondheim captured from the notes that I was able to scribble amid being completely enraptured and utterly fascinated by the brilliance that was emanating forth from the stage.

The evening commenced in earnest with Stephen Sondheim’s entrance, which was greeted by an immediate standing ovation to which he said, bemused, “It’s all downhill from here!” Suddenly, the tail end of “Happy Birthday to You” rings out over the theatre from the balcony and Sondheim says, even more amused, “Why does everyone sing that in E-flat?” before offering a heartfelt thank you to his captivated crowd.

The first question that Robert Cushman asked was when and how Sondheim started writing music.

SS: I didn’t know that I was going to write music, but, as many of you probably know, I developed a close relationship with Oscar Hammerstein (II), and he became a sort of surrogate father to me. I had taken piano lessons when I was around seven, but not for very long, and I liked music, but I had no desire to write any of my own. And then my parents got divorced when I was ten and I fell into the Hammerstein Universe and then, because he was a surrogate father to me, I wanted to do whatever Oscar did… and he wrote songs. Oscar wrote the lyrics to songs, but when I started to write my own, it just never occurred to me to get another composer to write the music. What a lot of people don’t know is that although Oscar wrote lyrics, he always had music in mind for the words he was writing. It usually wasn’t his own music, and he didn’t tell (Richard) Rodgers. It was usually some Stephen Foster tune… Oscar had this one gimmick he could do, he could play “Jeanie With the Light Blond Hair” with the left hand and… some other song I can’t remember with the right. That was his party trick. … So, I wanted to write a show for school and I just didn’t think of anyone else who would write the music.

Robert Cushman asked him what kind of music he was listening to while he was growing up.

SS: I was listening to songs from shows, but I may not have known that they were from shows. My father was an amateur piano player and he could pick out the tune and the basic chord structure of a lot of the popular Broadway songs, so the house was full of show tunes, but I didn’t know that that’s what they were. I also really liked listening to… what we would probably call concert music when I was about ten or eleven. I’m a romantic, for me music starts with Brahms and ends with Stravinsky, with a little bit of Bach in there. So, I was learning a lot through osmosis, and I started writing music imitating Rodgers with “It Might as Well Be Spring” or “The More I See You” and I would steal bits from that. That is the way you learn, through stealing. There’s a saying, talent borrows, genius steals, because when you steal something like that, it becomes your own. (As he segues from this thought back to Cushman’s initial question he says) I’ll just ramble, it’s what I do. I remember hearing Lenny (Leonard) Bernstein play and he would say upfront, admittedly, “It’s just Brahms,” and yes it was, but it was also Bernstein. He had digested the music and the fact that it had originally came from Brahms was not the point, it was now Bernstein because it had been digested by him and he made it his own. When I was fifteen I was at the George School, a prep school, a co-ed school, and I wrote a show about the school, with thinly disguised faculty members and students appearing in it, called By George… I was clever even then. I wrote the music and this girl wrote the lyrics with me and this boy wrote the book. And, at this time, Rodgers and Hammerstein weren’t just writing musicals, they were also producers. They had produced Annie Get Your Gun that year, in fact, and so of course, I thought that they could produce my show. I thought it was really good. It had this big love song in it, the school had this round seated area with a big pillar in the middle and between 5:30 and 6:30 the girls and boys, it was co-ed school, would meet there for what we actually called “fussing.” And they called this place The Donut, so the song was called “I’ll Meet You at The Donut.” It was a sincere and heartfelt love song. When (James) Lapine was working on the show that they call Sondheim on Sondheim I told him, “you have to use The Donut.” Anyway, I was sure that I was going to be the first fifteen year old to have a show on Broadway. So, I told Oscar that I wanted him to read the script and to tell me, honestly, what he thought of it, as if he didn’t know me, as though this was just any old script that happened to come across his desk. Oscar said that the script was the worst thing that he had ever read, and then, because he could probably see my lower lip trembling, he said it wasn’t that it was without talent, but he also said that in his professional experience he had never read anything so incompetent. But, he really treated me like an adult, and we went through the script, starting from the first stage direction, I think we only got through the first, maybe, eight pages in three hours… but, and I have said this before, I learned more in those three hours than most songwriters learn in a lifetime because I was getting the distilled experience of Oscar and he was taking me and my work very seriously and because I was fifteen my brain was like a sponge and I just soaked everything up. The principles that he taught me then are still very relevant; and I write about them in the book. He told me to first take a play that I liked and to turn it into a musical, then to take a play that I liked, but that I would like to see improved, and to turn that into a musical, then to take a story that wasn’t a play, a short story or a novel, and to turn that into a musical and then to write a musical entirely of my own. So at the end of that, I had four shows. And that was within five years, I finished the last one in my last year of college.

RC: For those did you write the books as well?

SS: Yes and I think playwriting is the hardest. I’ve only written one play and it was a murder mystery, so it wasn’t even really a play… but especially writing a libretto, you just have so little space, and the music takes up so much air, and even when you’re writing the book toward the climax, you never even get to write the climax because that is where the song goes! So, not only do you have the hardest job, but you also have no joy. Also, if a show is bad, the critics usually attack the book first, so no, I don’t write the books of musicals anymore. When I meet with librettists the first thing I usually ask, or that we usually talk about is, “Why should this be a musical? How will the music fulfill the story?” Because, otherwise, the music is just decoration, and some very successful composers write like that, but I think that the songs have to help shape the story. Usually the problem we run into is having too many ideas, and sometimes they get paired down into just a few lines, or one scene, or a bit in the music. The art is HOW the songs should function (in the show), WHERE and HOW and I think not attending to this question is one of the basic mistakes a composer can make.

RC: Can you give us an example of a basic mistake?

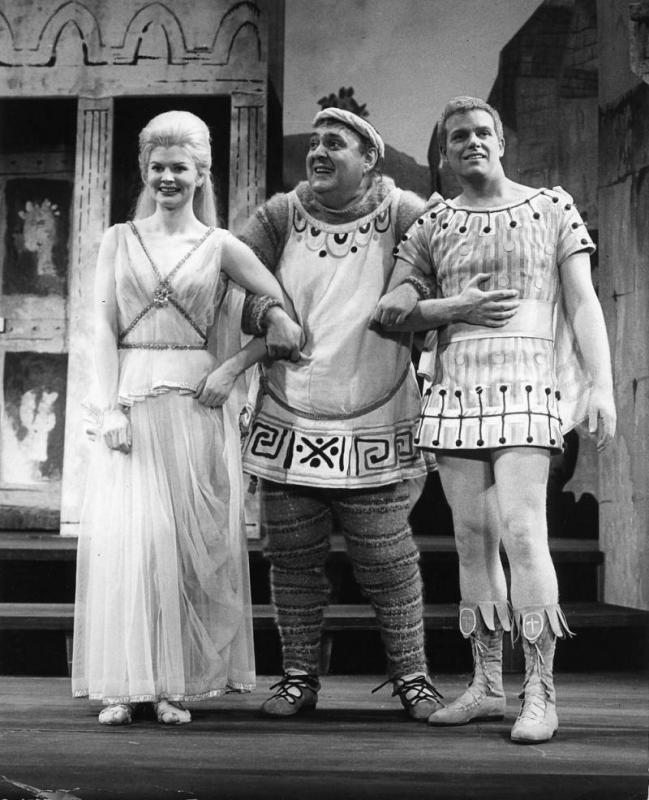

SS: Yes. Forum. I agree with what Des (McAnuff) said (that A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum is one of the best farces ever written) and actually I would go further and say that I think that Forum is the best farce ever written. It is so intricately woven by (Burt) Shevelove and (Larry) Gelbart. It was the first show that I had written both the lyrics and the music and I was nervous and I kept thinking that something was wrong with the show, but I couldn’t tell if it was just me being neurotic or if there was actually a problem. I asked James Goldman to read the script and listen to the score and to tell me if there was something wrong. He thought that the script was brilliant, and he said that the script “sparkled” and I was immediately relieved and said, “Oh, so there’s nothing wrong!” and he said, “Oh, there’s a problem. They don’t go together.” The script was this low comedy farce, and the songs, with the exception of “Impossible,” were too elegant with sophisticated rhymes. I had just come off West Side Story where the characters couldn’t rhyme more than “pay” and “day,” and Gypsy, which was better, but still colloquial, so I didn’t have any chance to show off! But, I had written these songs in the wrong style; both aspects of the show worked on their own, but we couldn’t put them together. It’s possible to write something that is good that is wrong, and it takes just as much effort to write something wrong than to write something right. But, since Des is doing the show here, I assume that he’s fixed the problem….

What I needed to do to fix the show was write “Comedy Tonight.” It would be better if I could go back and do it again. But, actually, we opened out of town and George Abbott was the director and he was considered at that time to be the “King of Comedy” and the show was a huge disaster. And George Abbott was also a play doctor in those days, where if your show wasn’t working when it played out of town, you’d call in George Abbott and he would save it for you. Well, for Forum, the audience was not having a good time even though we thought that the show was hilarious and we had good actors. So, one day George said to us, “Fellas, I don’t know what to do, you better call in George Abbott.” And we did, and his name was Jerome Robbins. He said that the show needed an opener… one that you could hum (pause) I’ve heard that a lot… and that it needed to establish that the show the audience was about to see was a low comedy farce. And he said, “No jokes. Let me do the jokes.” And so I wrote “Comedy Tonight,” which basically says the same idea over and over, but after that, Forum became an overnight hit and the way that Jerry staged “Comedy Tonight” was brilliant.

RC: What was Jerome Robbins like to work with?

SS: Impossible. Well, if you were a dancer. No… he was difficult. He wanted… he strove for perfection. Although, we all do, I don’t think that’s what made him different. He thought the world was against him. He had this paranoia, especially because he was not well educated, so when he was around me and Arthur (Laurents) and Lenny, he would get defensive. He also had this habit, this bad habit, of using one of the girl dancers and one of the boy dancers as his whipping posts and he would humiliate them in front of the company which created a sort of tension, an energized tension, but that was unpleasant. I thought that after 6pm, he was a lovely, charming, wonderful guy to be around… but between 9-6pm- stay away.

RC: Surely Leonard Bernstein had enough experience to stand up to Jerome Robbins?

SS: No. There were very few people who would stand up to Jerry. I remember during West Side Story regarding the orchestrations for “Somewhere” Jerry thought that there was too much rhythm and during the dress rehearsal Jerry walked down the aisle, tapped the conductor on the shoulder and told him to cut the clarinets and he proceeded to dictate the orchestrations to the orchestra while the cast was onstage and Lenny was in the audience. So, the next thing I knew, I looked for Lenny and his seat was empty, so I went out to the lobby and he wasn’t there, and I had a hunch, so I left the National Theatre and I went to the nearest bar and sure enough, there was Lenny with four shots of scotch in front of him. He just could not face Jerry. The only people I knew who could were Jule Styne, of all people, and Arthur Laurents. Jerry was so fierce.

RC: Did he scare you?

SS: Oh yeah. But, like many have said, I would do a show with him in an instant if he were here right now. He humiliated me twice in public and it was… very unpleasant.

RC: When you write the lyrics and the music you don’t have to ask which came first because we assume that they come together-

SS: Why do you have to ask anyway? (pause) I had the opportunity to look at some of Cole Porter’s notebooks and I was thrilled to see that he, like me, wrote out the words with rhythms, with no notes… no pitches. Then, I assume, he would go to the piano and decide. First comes the rhythm and the inflection. But, yes, the music and the lyrics come together, sure. I’m sure that (Irving) Berlin wrote the same way too. The musical and lyrical quality of the line suggests a pitch; it comes from the inflection… everything we say is a tune.

Robert Cushman mentions that he thinks that the lyrics to A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum are Sondheim’s funniest.

SS: I don’t think the songs from Forum are my funniest. The only line in the lyrics that I think is really funny is “I am a parade” and that is a direct quote from Plautus. I think that the songs in Gypsy are funnier. “Gotta Get A Gimmick,” that’s funny. The funniest jokes come from situation and not from one liners. Like in “Adelaide’s Lament” (from Guys and Dolls), it’s not the words that she is saying (that are so funny), it is the situation that she is in with this man who she wants to marry and her character which makes that song screamingly funny. And it is the attitude of those ladies in “Gimmick”, “Once I was a schlepper, now I’m Miss Mazeppa…” that’s funny.

RC: Which would offend you more a bad rhyme or a wrong stress?

SS: It’s not really about offending, a bad rhyme will kill the line, and a wrong stress won’t, it will just annoy purists like me. A wrong stress just lessens the impact. It would be like saying, “To be OR not to be,” and you would think, “Well, that’s very good, but something is wrong.”

Robert Cushman makes a parallel between the artificiality of Shakespearean verse and the songs in musical theatre, saying that in both the audience has to attune their ears and suspend their disbelief because these conventions are so different from the way that the real world works.

SS: I don’t think that anyone who watches a musical theatre show is concerned with the suspension of disbelief. That is what we all do when we go into the theatre, and we know that. All theatre, all plays, have a sort of artificial language. I don’t think anyone in the audience is sitting there thinking, “she wouldn’t really sing that!”

RC: Even Oscar Hammerstein’s characters don’t speak the way most people do.

SS: Rodgers and Hammerstein shows weren’t about the language. Their musicals were new because they were trying to tell the story through song because before Oklahoma! musicals were slightly elevated reviews where the jokes that were being told in the book didn’t really relate or connect to the songs that were being sung. What Rodgers and Hammerstein did was to reduce the sorts of songs that were in operetta and to mix them with musical theatre writing and to approach musical theatre as though it were a play. Oscar was never very good at writing in a contemporary style. For example, Me and Julia, is kind of embarrassing for that, because he has people calling each other “bozo” and all these twenties sayings. He had no sense of the way that people actually spoke. It was in dialect and period pieces that he really succeeded with. But, I also went to see a very successful production of South Pacific recently and thought to myself, as they’re singing “There’s Nothing Like a Dame”, that no soldiers would ever be caught dead talking like that… actually it seemed in general to be the happiest war in the history of the world. I think that his strongest work was really done in Oklahoma!,Carousel and The King and I. But, I think what was most important was what Oscar did as a playwright. Gypsy was really a culmination of the Rodgers and Hammerstein way of writing musicals. You don’t really think about it because it became such a convention, but what Rodgers and Hammerstein did in their time was really very innovative.

Robert Cushman alludes to the fact that Sondheim’s musicals are quite different in their construction from a show such as Oklahoma!.

SS: When we were writing Company we thought, “maybe you could have a show with a story and no plot” and that’s exactly what Company is. It is a series of vignettes, like a scrapbook of Bobby, and it adds up to a revelation, the same sort that Oedipus experienced. Bobby learns something in Company that he doesn’t know at the beginning. But I think Gypsy, and maybe My Fair Lady, they were the culmination of the musical theatre book musicals. Also, playwriting was changing around this time as well, and writers were beginning to break away from the well-made play, the plays written by people like Lillian Hellman, she had a plot, and suddenly the new trend in playwriting was to try something different.

RC: Could Fiddler on the Roof also be considered an example of a musical from that genre?

SS: Yes, I think Rodgers and Hammerstein could have easily signed their names to that.

Robert Cushman asks Sondheim about the lack of ambiguity in Rodgers and Hammerstein shows, Sondheim asks if he is talking about irony and Cushman responds that it seems like Sondheim’s characters don’t always know their own emotions.

SS: Bobby never knows what he feels, that’s the point of Company.

Cushman says that Rodgers and Hammerstein characters, and those of that elk, have a penchant for expressing themselves clearly in song and telling the audience exactly what they are thinking and feeling.

SS: That’s what would have been called in Shakespeare a soliloquy. I think that what you’re asking about is subtext, and that is what I have thrived on. That’s what playwrights do. They give something for the interested members of the audience to uncover as they delve beyond the surface. That’s why when you read Chekhov, you think, “Nothing is happening!” but then you’re crying. Music can supply subtext like nothing else can. Why does music get to you like it does? I think our bodies must just be hardwired for it. Subtext makes the theatre thrive, and in musicals it makes the book more interesting and more complicated. Oscar actually had the opportunity to do Pygmalion, someone approached him and Rodgers about adapting that play and he said, “It all takes place in one office; that’s not musical.” He didn’t see what was going on underneath the surface. I think that most characters in musical theatre are one and a half dimensional… maybe two and a half at most. But you can give subtext in music, for example you can tell, musically in “The Road You Didn’t Take” (from Follies) that Ben is not telling the truth. In Anyone Can Whistle, the part that Angela Lansbury played, she is singing this snappy song with four boys about how the people are starving, the people are STARVING. That’s ironic. I’ve made a semi-career out of that.

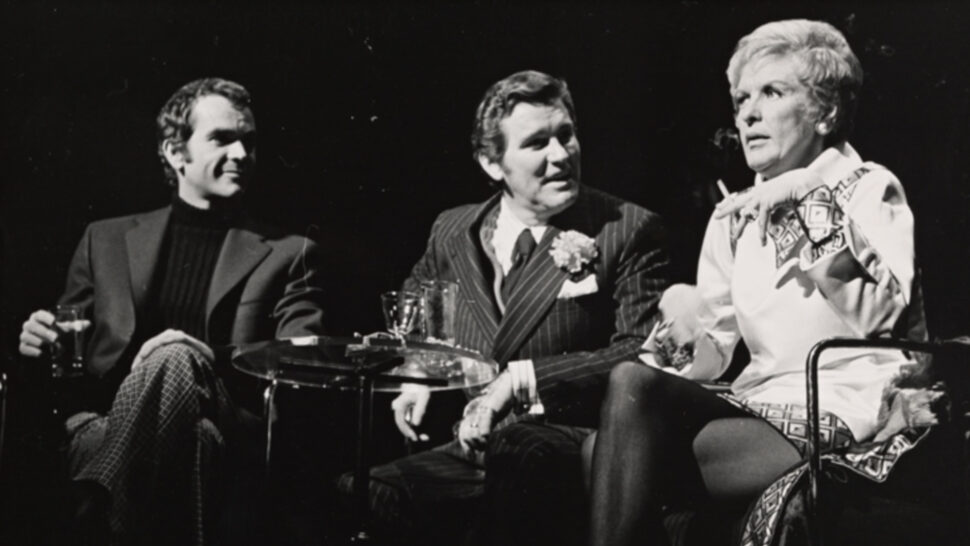

Cushman asks Sondheim about the development of Company (1970).

Friedman-Abeles/©NYPL for the Performing Arts

SS: George Furth, an actor, went to his shrink and was told that he should write out his feelings in the style of a play, so he wrote a series of one act plays that were all between ten and thirty minutes long. There were eleven of them and seven were chosen to be produced as part of an evening of short plays. They all centreed on this lead couple and then there was always, in various forms, this outsider. Hal (Harold) Prince, a very savvy producer, came on board and said that the plays should be adapted into a musical, and I said, “Oh? How can seven disparate plays be a musical?” But then we decided to take all the various outsider characters and make him one person. We invented Bobby, and he became the catalyst. We asked ourselves, “why is he there?” and came up with the answer that he was examining marriage. The show actually takes place in thirty seconds—

Robert Cushman brings up that this “concept show” (although Cushman doesn’t use the words “concept show”) was a new and experimental way of writing musicals.

SS: Well, it’s only considered “experimental” because it was a success. If it had failed people would have looked at the idea and said, “No, we can’t do that, look what happened to Hal and Steve’s show.”

Cushman asks Sondheim about one of his personal favourite shows, Into the Woods.

SS: We were interested in the idea of examining the relationship between the parent and the child. Folktales are made up of fatherless children; most of the characters in the show don’t have fathers. Where is Jack’s father? And that led us to the idea of community responsibility. We all caused these tragedies. But then again, we never say when we’re starting out, “This show will be about COMMUNITY RESPONSIBILITY,” but once you get into the work, then you start asking the questions, “what is it that we are asking the audience to focus on?” Sometimes you don’t find out until the show is on the stage. You would never write a song and then say, “Oh, wait, this isn’t about our theme– COMMUNITY RESPONSIBILTY– Better throw it out!”

Cushman brings up the death of the Baker’s Wife in Into the Woods saying that it is surprising because usually characters who die in musical theatre are either ones that the audience is not supposed to like or ones that are going to come back in Act II.

SS: James (Lapine) plotted the book of Into the Woods perfectly. He actually, the way he did it, he started in the middle and I said to him (from all my PROFESSIONAL experience) “Listen, let me tell you, you have to plot each character out in detail, like on a graph” and blah blah blah. And of course, James got blocked and he came to me and said, “Let me just try it my way” and of course it ended up brilliantly plotted. It is a fresh and inevitable story. It’s the only thing that could happen, and yet you’re completely surprised.

Cushman brings up how popular Into the Woods is, especially among younger audiences and schools.

SS: Yes, we said, “if this show works, it’s our annuity.” And it has been done a lot in schools, and since there are no four letter words, there’s none of that horrifying censorship that sometimes happens. Also, everyone has something to do, which makes it a good show for schools, rather than a show that has maybe four or five principle roles and then a large chorus. What I’m surprised about is that after Into the Woods, the second most popular show of mine for schools and colleges is Sweeney Todd, which is a powerful show, but my goodness, it’s hard to do!

Cushman begins to ask questions from the audience, written on index cards. The first one is “what is the most satisfying aspect of your artistic process”?

SS: (after thinking about his answer for a moment) I’m just going to say what comes out from the top of my head, otherwise I’m just going to sit here and think all night. I think that it’s when a lyric just sort of zooms into my mind, like a boat docking, and it is perfect. In music there is usually more than one possibility, but lyrics it’s more of that boat coming into port.

RC: (from audience) What direction do you see the future of musical theatre going?

SS: I don’t see any future. (pause/ laughter) No, I mean, I think that we see trends in musical theatre and things like that in an overview in hindsight. We’ll know in ten years when we can look back and examine the trends. Right now musicals trends are being dictated by economics, producers don’t want to take a chance on unknown songs written by unknown songwriters, so they produce jukebox musicals, ones that have songs that the audiences can hum on their way INTO the theatre. Also popular right now are what we call meta-musicals, shows that are very aware of themselves as being musicals and say things like, “look! This is the opening number!” and they let the audience know that they are in on the joke. There are not too many producers who are investing in fresh stories that we haven’t heard before… and that’s too bad. Although, these shows tend now to emerge from Off-Broadway and the regional theatres and if they get good reviews sometimes they can transfer to Broadway, like Spring Awakening did. Sometimes these shows have good runs there and sometimes they don’t. Although, I will say that now in musical theatre you can write anything, there are no rules. Experimentation is the name of the game, and that’s healthy.

RC: (from audience) Would you ever consider writing an opera?

SS: I’m not an opera fan, just the fact that it takes them ten minutes to sing, “I’m taking out the garbage.” And the people who go to the opera, they’re not going for the story, and most of the time, they’re not going for the music, they’re going for the performers, like people going to a rock concert. In opera it is about the singer not the song, and I focus more on the song and not the singer. I’m also not a big fan of the sung-through shows. I like having a book.

RC (from audience): Why are the lyrics for “America” different in the stage play and the film version (of West Side Story)?

SS: Originally I was writing “America” for Bernardo and Anita to sing, because he resented living in America and she liked it and it was an opportunity for two principle characters to tell the audience a little more about themselves through song. But Jerry said, “No, I want it to be just girls.” I felt like I couldn’t make an argument for the song to work without Bernardo, but then Arthur invented Rosalie to take Bernardo’s point of view and it changed the scene to all girls. But when we were working on the screenplay I went to Jerry and asked if we could do the song between Bernardo and Anita, and he said “Okay,” that it might be nice to have the boys and girls dance together, so actually the lyrics in the film were the first lyrics that I wrote for the musical when it was going to be Bernardo and Anita.

RC: Couldn’t you change the scene in the musical now to the way you had originally conceived it?

SS: No, you have to have all of Jerry’s choreography or none of it, it’s in his contract, so, guess what…

RC: (from audience) Is “Someone In a Tree” (from Pacific Overtures) still your favourite of your songs?

SS: Oh, that’s just been the standard answer that I usually give to that question. I do like that it contains the present, past and future all in one number, and also I wanted to see how long I could vamp in a song before the audience got up and left. I also love “Opening Doors” (from Merrily We Roll Along) because it’s semi-autobiographical… that spirit of the young songwriters, I can relate to that. People think that a lot of my characters are based on me. They think that I am George or I am Bobby… actually the only character that people don’t compare me to is Kayama. But really, the only characters that I see myself in are, I guess the two songwriters in Merrily and George when he sings “Finishing the Hat,” the idea of trancing out into intense concentration, where the world disappears and you have entered the universe of the creative people.

Robert Cushman asks Sondheim how he writes his characters if he isn’t basing them on himself and connecting to them autobiographically.

SS: I do exactly what actors do, I inhabit the characters until I know them as well as I know myself. I begin to talk as the character, like the character. It comes easy to me because I am a rather good mimic, that is a talent that I have.

RC: (from audience) How have advances in technology affected your writing?

SS: Technology doesn’t affect my writing, that is something that affects the director and his choices more than anything. Sondheim on Sondheim was a sort of technical marvel for James. I also just haven’t had the opportunity to write toward a technical thing. Maybe if I wrote a science fiction musical…

Cushman asks if Sondheim has anything else to say about Into the Woods.

SS: Yes, actually I do. This story is kind of fun. James and I were talking about writing a TV special as a way to make some money and we were talking about taking all the sitcom characters on television at the time, Ralph Kramden and Carol Burnett’s characters and Archie Bunker and having them meet in a hospital, and we would get all the actors to play them, and that way we wouldn’t need any set up because the audience would already know them. So, then James and I were thinking “let’s sell this to the network” because we didn’t want to actually write it. So, we pitched it to the executives who liked the idea and wanted us to start work on it- and basically it came down to either we write it or the project gets abandoned. But then James and I started to talk about a new musical that we wanted to work on, and I had said that I had always wanted to write a Wizard of Oz kind of fairytale or folktale and so James went away and thought about it and finally said, “The possibilities are infinite!” So, I knew I wanted it to be a quest story, so I had to ask myself “what was the quest?” and then we thought what if we took the sitcom idea and applied it to Fairy Tales….

Cushman asks Sondheim what made “Send in the Clowns” (from A Little Night Music) such a hit song?

SS: I have no idea. And it took two years. At that time the charts were mostly made up of rock and pop songs, hit songs did not come from musical theatre. So, the song lay fallow for two years and then Judy Collins recorded it and it became a hit, not so much here, but in London. And then Frank Sinatra recorded it and I don’t think there’s any reason why that particular song, it’s just as humable as “Losing My Mind”, which never became a hit, well not until Liza Minnelli did it with the Pet Shop Boys and that was thirty years later. I used to get so many letters, not so much anymore, from people saying, “I love this song… what does it mean?” because people were unfamiliar with the theatrical culture and the idea of clowns. “If you go out with a chick and it doesn’t work out… send in the clowns.”

RC: (from audience) Is there anyone you haven’t worked with that you would like to?

SS: No. No, there are people who I think are talented and do good work but, there’s no one that I lie awake wishing to be able to work with. I’m not hungry.

RC: (from audience) What do you think about people doing your shows in other languages abroad?

SS: I never say no, I am just happy that someone wants to do it in a different country, but sometimes they send me the literal translation and if the lyric gets distorted… it gets distorted.

RC: (from audience) What makes a good cast album?

SS: It should convey the excitement of the performance, and capture the spirit of the piece. If you’re really listening to the opening song in Company… what is that note that Elaine (Stritch) is singing? But it doesn’t matter, and the album is terrific.

RC: (from audience) What is your favourite unsung song?

SS: Presumably they mean, un-recorded song of mine. (pause) If I said, you wouldn’t know what it is. What a Lewis Carroll question.

RC: (from audience) If you didn’t live in New York where would you live?

SS: In America, I would say Chicago, just because there seems to me to be a spirit of joy in Chicago, but I have only ever been there for two weeks at most, so maybe if I moved there that perception would change. Outside of the country, I would have to say London.

Shortly thereafter, the index cards having run out, Stephen Sondheim, filled with grace and humility arose from his chair and, his eyes filled with warmth and gratitude, stood before his wildly applauding public. I am looking forward to Mr. Sondheim returning to Toronto hopefully in the near future, and am filled with anticipation already for the celebration of his next milestone birthday. It is so reassuring to know that there are true legends out there and that in the case of Stephen Sondheim, he is dedicated to imparting, a least through dialogue, a bit of his experience, his genius and his brilliant insights with the younger generations of artists and audiences to build a bridge between our generations, one that links us both to our proud past and our shining bright future. I know for absolute certain, no matter how far I roam, what adventures come to greet me along the way, Steve Sondheim will stay in my heart forever.

World Theatre Day: My God Is It Ever The Time to Invest in Canadian Plays

World Theatre Day: My God Is It Ever The Time to Invest in Canadian Plays