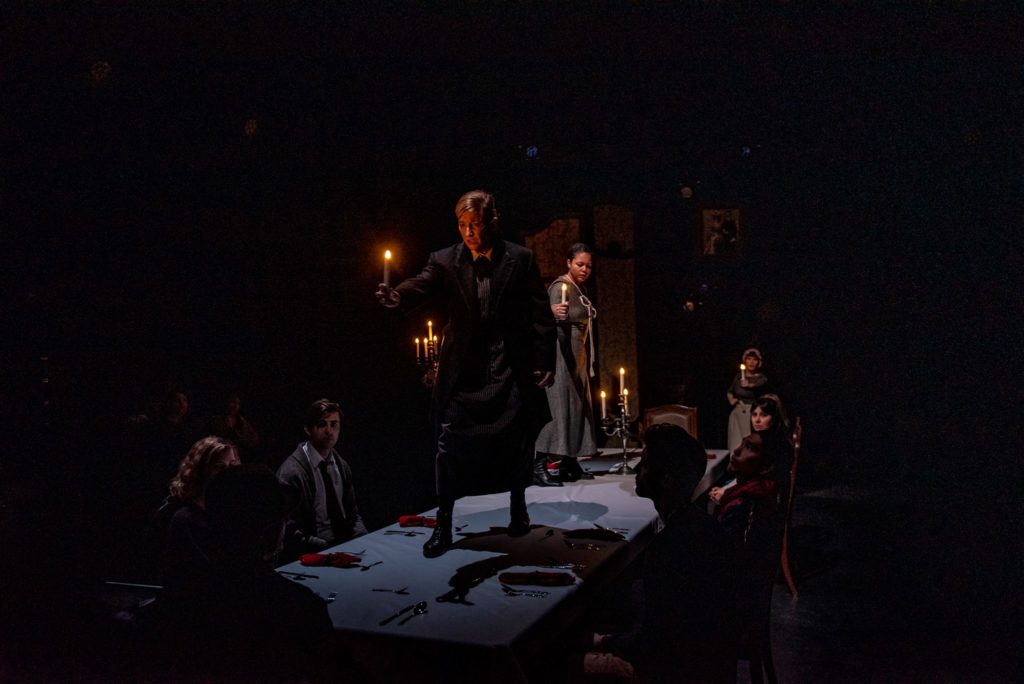

jackie torrens & micha cromwell photo by: stoo metz

Hamlet was written by William Shakespeare over four hundred years ago, and has been produced steadfastly all over the world ever since. It’s incredible that theatre artists and scholars are continually able to find new insights into its text, new ways to tell the story, and different lenses through which to make Hamlet relevant to the politics and culture of the day. In a recent article in The Coast about Below the Salt’s production of Hamlet, playing at the Neptune Theatre Scotiabank Stage until January 20th, director Ken Schwartz says, “When you stage a classic piece of work, the first question you have to ask yourself—and it’s obvious—is ‘Why? Why do it again?… It’s been done a million times, it’ll be done another million times—what do you have to say that’s slightly interesting to bother doing it again?” As someone who writes about the theatre the “why” is always one of my most pertinent questions, but the moment I saw Jackie Torrens on the poster for this production, the “why” was immediately clear. Although this text is over four hundred years old, it’s still rare in the professional theatre to see one of the canon’s most iconic roles being played by a woman.

The concept of Below the Salt’s Hamlet is that we have gathered at an Edwardian dinner party, but the hosts have been inexplicably delayed. Their serving staff of six decide to entertain us while we wait by performing Hamlet. They have to make some creative adjustments, since there are only six of them (five women and one man), some will have to play multiple roles, women will need to play men, they will use the dining hall as their stage, largely finding ways to tell the story around a large dining table (where some audience members are seated), and they will have for props only the objects that they have in their immediate vicinity. In this way, at all times each of the actors are playing two roles, as the portrayal of the characters in Hamlet are being projected through an unnamed server character, about whom we know nearly nothing, except that they are an extremely skillful amateur actor. Hamlet is, of course, a tragedy, and the story remains so in this production, but there is a joyful sense of play and of ingenuity in the way the serving staff bring the story to life that lifts up the comedy inherent to Shakespeare’s work, and gives a sense of urgency and freshness to the story.

Sarah English plays Laertes, Matthew Lumley plays Polonius and Micha Cromwell (often) plays Ophelia, and they quickly establish a lovely familial dynamic. Lumley gives Polonius a “dad voice” that roots his pedantic speech to the departing Laertes firmly in our own time. English’s Laertes then nicely mirrors this in her own cautionings to Ophelia, and you can see the conflict in him between wanting to connect with his sister as equals, but also feeling as though it is his duty as an elder brother to seek to control and shape her, as his father has sought to control and shape them both. In this way, we really see that it’s Polonius’ arrogant and meddling “Father Knows Best” attitude that gets him killed, but, that it does come from a place of love and good intentions, as he leaves behind two genuinely devastated children. English’s confused anguish as Laertes upon returning to Denmark and finding his father killed and his sister descended into madness is especially poignant. Cromwell’s Ophelia also beautifully oscillates between her inclination to reach out to her father and brother with affection, and the resentment and disappointment she feels when her youthful exuberance is met only with cold finger wagging. In Cromwell we see Ophelia first as keeping guard over her emotions and expressing herself clearly rooted in logic and forethought. In her “madness” her emotions have been unleashed and she is unpredictable and uncontrolled, which we see is both horrifying and threatening to the men around her. Cromwell finds the empowerment in this moment, which makes Ophelia’s death all the more tragic.

One aspect of the production that is confusing and interferes with the arc of Ophelia’s journey, and the establishment of her relationship with Hamlet is the choice to have Ophelia played at times by actors other than Cromwell.

Geneviève Steele plays Queen Gertrude and Burgandy Code plays Claudius and the most striking choice for me was how intimate and in love these two characters were. This choice adds a layer of questions of complicity for Gertrude. Was she in love with Claudius before her husband was killed? Were her and Claudius involved before King Hamlet’s death? Or, did she genuinely fall in love with Claudius because he was so kind and supportive of her while she was a grieving widow? Steele also shows Gertrude’s genuine love and concern for Hamlet, but also her complete bewilderment at his behaviour. It is as though she cannot fathom why on Earth he would be upset about his mother marrying his uncle two months after his father’s sudden death. Code’s Claudius is a complex one. He doesn’t seem at all like a cold-hearted brother-murdering monster. Initially, he even seems to warmly want to welcome Hamlet into the family he has made with Gertrude. He seems to love Gertrude passionately, and even seems to hint at feelings of guilt for what he has done to his brother. Yet, as the stakes for his survival mount, Claudius becomes increasingly sinister, which raises the question whether he is operating from desperation for self-preservation, or whether he is a sociopath skilled at imitating affection. Much has been discussed about Hamlet being an “over-thinker” but Code’s Claudius also struck me as a bit cautious in the same way, which I found very interesting. It would make sense that Hamlet and Claudius might share certain personality traits, considering they are so closely related, which suggests to me that perhaps the only difference between Claudius and Hamlet are their exact circumstances and their choices. It also raises the question of how different, ultimately, is Hamlet, who kills his uncle, from Claudius, who kills his brother?

Hamlet is played by Jackie Torrens, and what I love about this Hamlet is that you really get to see moments of what Hamlet was like before his father died, and in those brief flashes he is so immediately likeable, that it roots you securely on his side, however dubious his quest may be. We see these moments shine through his grief with his best friend Horatio (beautifully played by Cromwell) and the watchmen, in his interactions with his father’s spirit (played in clever doubling by Code), and when the players (English and Cromwell) arrive. It’s clear here that it’s Claudius’ presence in Hamlet’s life that is exacerbating his grief and melancholy. I found it very clear that Torrens’ Hamlet uses his cover of madness as an excuse to be able to openly and honestly express his feelings of anger, resentment, and helplessness in the face of injustice. Hamlet calls out each of the other characters for their pretence. Some are dishonest on purpose, and others are adhering to societal norms which seek to repress authenticity in the name of modesty, propriety or ambition. Torrens finds moments to let Hamlet’s dark sense of humour out, to showcase his insights and his intellect. As the play goes on Hamlet is less the brooding Dane full of self doubt, and more a gleeful puppet master trying to dodge death and trick Claudius into a confession. He has moments of pure triumph, which makes his missteps all the more tragic. Although Torrens’ Hamlet does and says all the same things that Hamlets have been saying and doing for four hundred years, Torrens finds ways to subvert expectations, to surprise and to make connections that were new to me. I felt like I was meeting a Hamlet I had never met before.

In the late Victorian Era women began attending matinees of plays, which led to some women forming play reading clubs in their homes. Some of these clubs were more theatrical in nature than others, and in some cases, they led to the development of amateur theatres. Schwartz’s concept for Hamlet reminded me of these clubs, but this production also adds the important element of class. The Victorian women who had the leisure of attending plays in the middle of the day would have been akin to the “hostess” of Schwartz’s fictional dinner party. Instead, we are treated to a performance largely by women who would not have had the same opportunity to attend the theatre or to have pursued their interests by forming a club with their friends. Here, these servers are at work and, unbeknownst to their bosses, they’ve had to seize on an opportunity at random for themselves in order to tell this story. The Edwardian period was marked as a transitional time when the working classes were able to break out of crumbling social structures to make better lives for themselves and their children. So too, does it seem, that we are living in a time when further social structures appear to be shifting, and again, it is largely the workers, and those on the margins, who are working toward making the world more equitable and just for everyone.

Below the Salt’s Hamlet is simultaneously set over 100 years ago, over 400 years ago, and in a time unspecified by Shakespeare, but it feels relevant to 2019. It feels new and triumphant, and also a bit ominous and cautionary. If you enjoy your Shakespeare shaken up, as I do, this production of Hamlet allows you to consider the play with fresher eyes, while still doing beautiful service to a four hundred year old work often considered one of the most influential in world literature.

Below the Salt’s Hamlet runs now until January 20th, 2019 at Neptune Theatre’s Scotiabank Stage (1593 Argyle Street, Halifax). Shows are Tuesday to Saturday at 7:30pm with 2:00pm shows on Saturday and Sunday. Tickets are available HERE. Seating is limited, there are 115 seats available in the auditorium and 16 on the stage.

World Theatre Day: My God Is It Ever The Time to Invest in Canadian Plays

World Theatre Day: My God Is It Ever The Time to Invest in Canadian Plays