In my Canadian Theatre class at Dalhousie University, as in my Introduction to Canadian Cinema class at the University of British Columbia, I often encountered the argument that themes of isolation, loneliness, the barren, cold winter and the wide sprawling countryside are characteristic to Canadian art. One need only read Gwen Pharis Ringwood’s Still Stands the House (1938) to see how these themes were spun into the first plays that sought to give voice to the Canadian experience. In 2009, however, writing plays about Canadian history and alluding to such things as our “national identity” or isolation, loneliness, the barren cold winter or the wide sprawling countryside can seem stereotypical and traditionalist. Yet, surely Canada has a rich past, fraught with untold, fascinating tales, and with ample inspiration to weave fictitious ones, it is doing so with creativity and originality that ensures that these stories will continue to resonant with contemporary audiences.

In The Mill Part I: Now We Are Brody Matthew MacFadzean has combined all of these seemingly stereotypical elements of Canadian National Identity and has woven them all elegantly into a play that is primarily about one specific place and one specific group of individuals. It is also a gripping ghost story that transcends Canadian history in its ability to captivate and disturb an audience, while also raising questions that are still extremely relevant in contemporary society. Who owns the land on which we have built our cities? At what great cost was Canada “settled” by its European conquerors?

Instead of pitting the present against the past, MacFadzean has brilliantly created Charlotte MacGonigal, a young Canadian settler who comes to reclaim the old abandoned mill built by her father in a town that once bore his name. It is 1854 and yet throughout the play Charlotte’s insight into the past that haunts the mill and the realization that her father, James MacGonigal, has committed heinous, atrocious, unforgivable actions to which all the citizens of Brody are complicit as long as they do nothing to recompense for them, mirrors our own contemporary relationship to Canada’s colonialist past.

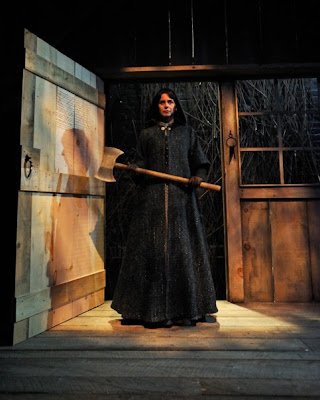

I found that Now We Are Brody was less terrifying than Part II of The Mill: The Huron Bride, and that in its violence there was a certain, although perverse, satisfaction and triumph. Nevertheless, Daryl Cloran’s direction was fascinating. The play opened with a long, extended series of scenes in which Charlotte (played by Michelle Monteith) was alone onstage with only sporadic dialogue. Cloran expertly built the entire foundation of the play on Charlotte’s movements and his lighting and soundscape choices, and was successful in building an ominous sense of dread wordlessly until the dramatic tension became so intense that only the entrance of another character could ease the audience’s apprehension. There was a particularly impressive bit of physicality for Maev Beaty’s Rebecca, as well as stunning visual tricks by Monteith’s Charlotte and Holly Lewis’ Lyca, which all elicited an electric combination of wonder and dread.

The performances in Now We Are Brody are just as brilliantly executed by the cast as in The Huron Bride. Michelle Monteith gives another charming performance as Charlotte, and is able to play with more creepiness than she had with Hazel Sheehan. She descends into her own dystopian Wonderland to glorious effect. The stage is Holly Lewis’ jungle gym as Lyca, who is every bit as creepy in Brody as she was in Jamestown. Ryan Hollyman gave a fantastic performance as William the Preacher, Charlotte’s vile and disgusting pig of a husband. Eric Goulem’s Alexandre and Maev Beaty’s Rebecca both appeared in The Huron Bride as well and both Goulem and Beaty were fantastic in their ability to infuse their respective characters with all the pain and secrets of the past depicted in Huron Bride, which takes place twenty years earlier. Beaty’s Rebecca has become a paranoid, stubborn, icy woman who refuses to let her guard down as she had once done with Hazel. Pain, fear and loneliness radiate from Rebecca mercilessly and ensnare her in a trap from whence she cannot escape. Goulem’s Alexandre still provides the comic relief to the play, but he is but a shadow of his former jovial self. He, like Rebecca, has obviously been traumatized and therefore cannot seize life with quite so much gusto. I wish that Matthew MacFadzean had made Richard Greenblatt’s character, Milton, Lyca’s grieving adoptive father, a larger role both because Greenblatt is such a fantastic actor it is a pity to have him offstage so much, and also because I felt like I wanted to know more about this man and his relationship with Lyca.

In The Mill Part I: Now We Are Brody Matthew MacFadzean has combined all of these seemingly stereotypical elements of Canadian National Identity and has woven them all elegantly into a play that is primarily about one specific place and one specific group of individuals. It is also a gripping ghost story that transcends Canadian history in its ability to captivate and disturb an audience, while also raising questions that are still extremely relevant in contemporary society. Who owns the land on which we have built our cities? At what great cost was Canada “settled” by its European conquerors?

Instead of pitting the present against the past, MacFadzean has brilliantly created Charlotte MacGonigal, a young Canadian settler who comes to reclaim the old abandoned mill built by her father in a town that once bore his name. It is 1854 and yet throughout the play Charlotte’s insight into the past that haunts the mill and the realization that her father, James MacGonigal, has committed heinous, atrocious, unforgivable actions to which all the citizens of Brody are complicit as long as they do nothing to recompense for them, mirrors our own contemporary relationship to Canada’s colonialist past.

I found that Now We Are Brody was less terrifying than Part II of The Mill: The Huron Bride, and that in its violence there was a certain, although perverse, satisfaction and triumph. Nevertheless, Daryl Cloran’s direction was fascinating. The play opened with a long, extended series of scenes in which Charlotte (played by Michelle Monteith) was alone onstage with only sporadic dialogue. Cloran expertly built the entire foundation of the play on Charlotte’s movements and his lighting and soundscape choices, and was successful in building an ominous sense of dread wordlessly until the dramatic tension became so intense that only the entrance of another character could ease the audience’s apprehension. There was a particularly impressive bit of physicality for Maev Beaty’s Rebecca, as well as stunning visual tricks by Monteith’s Charlotte and Holly Lewis’ Lyca, which all elicited an electric combination of wonder and dread.

The performances in Now We Are Brody are just as brilliantly executed by the cast as in The Huron Bride. Michelle Monteith gives another charming performance as Charlotte, and is able to play with more creepiness than she had with Hazel Sheehan. She descends into her own dystopian Wonderland to glorious effect. The stage is Holly Lewis’ jungle gym as Lyca, who is every bit as creepy in Brody as she was in Jamestown. Ryan Hollyman gave a fantastic performance as William the Preacher, Charlotte’s vile and disgusting pig of a husband. Eric Goulem’s Alexandre and Maev Beaty’s Rebecca both appeared in The Huron Bride as well and both Goulem and Beaty were fantastic in their ability to infuse their respective characters with all the pain and secrets of the past depicted in Huron Bride, which takes place twenty years earlier. Beaty’s Rebecca has become a paranoid, stubborn, icy woman who refuses to let her guard down as she had once done with Hazel. Pain, fear and loneliness radiate from Rebecca mercilessly and ensnare her in a trap from whence she cannot escape. Goulem’s Alexandre still provides the comic relief to the play, but he is but a shadow of his former jovial self. He, like Rebecca, has obviously been traumatized and therefore cannot seize life with quite so much gusto. I wish that Matthew MacFadzean had made Richard Greenblatt’s character, Milton, Lyca’s grieving adoptive father, a larger role both because Greenblatt is such a fantastic actor it is a pity to have him offstage so much, and also because I felt like I wanted to know more about this man and his relationship with Lyca.

I have heard some people criticizing The Mill’s use of projected credits at the beginning of the plays as a means to attempt to cinematize the theatre, but I thought that there was something extremely validating in seeing the names of our Canadian theatre artists in large font unfold across the set. The audience may not read the programme they are given by the ushers, but their brains will absorb the names of the artists if they are presented to them visually like we are used to seeing on television and at the movie theatre. I did feel, however, that Cloran’s direction was clear enough that we did not need the projections that told us that time was passing.

Charlotte MacGonigal has a line in Now We Are Brody that says, “This whole country is sorry. What good does that do? What good is sorry?” No matter how many grisly murders occur in The Mill, no matter how many ghosts seek revenge, our history proves that the mills that were constructed across our country in settlements like Jameston, were not torn down. Townships expanded into cities, and trees made way for pavement on which the descendants of William, the Preacher, and Alexandre Martiniques would soon build electric towers of immense size and impressive productivity. We are all still sorry. But a century and a half later, our words are still every bit as hollow as those of our ancestors. The spirits of the past remain in unrest, covered up and brushed aside, but still powerful in their ability to haunt us and to hold us all accountable for all we have done (and refused to do) that threatens to destroy the planet.

Charlotte MacGonigal has a line in Now We Are Brody that says, “This whole country is sorry. What good does that do? What good is sorry?” No matter how many grisly murders occur in The Mill, no matter how many ghosts seek revenge, our history proves that the mills that were constructed across our country in settlements like Jameston, were not torn down. Townships expanded into cities, and trees made way for pavement on which the descendants of William, the Preacher, and Alexandre Martiniques would soon build electric towers of immense size and impressive productivity. We are all still sorry. But a century and a half later, our words are still every bit as hollow as those of our ancestors. The spirits of the past remain in unrest, covered up and brushed aside, but still powerful in their ability to haunt us and to hold us all accountable for all we have done (and refused to do) that threatens to destroy the planet.

Theatrefront’s The Mill Part Three: The Woods by Tara Beagan, directed by Sarah Stanley featuring Frank Cox-O’Connell, Eric Goulem, Richard Greenblatt, Ryan Hollyman, Michelle Latimer, Holly Lewis and Michelle Monteith comes to The Young Centre in March 2010. Now We are Brody and The Huron Bride also return for limited engagements.

Next season The Mill continues with Part Four: ASH by Damien Atkins directed by Jennifer Tarver and then the entire Mill Cycle will play in repertory.

This is certainly a theatrical adventure you do not want to miss!