It has been said that when Nora slammed the door in A Doll’s House the reverberations were felt across the modern world. Henrik Ibsen’s groundbreaking play was written in 1879, and one would think that in one hundred and thirty years, the themes of this play would no longer resonate ardently within contemporary society. One would assume that the moral ambiguities that Ibsen raised in his Victorian play would be reduced to mundane commonalities by 2009, and yet, as I sat in the audience of Florence Gibson’s new play Missing, which plays at the Factory Theatre until April 5th, I was struck about how torn we still are (and I think rightly so) about the repercussions of that slammed door.

Evelyn MacMillan has disappeared, vanished into a fallow field one ordinary day in an unspecified year in the 1970s. Gibson’s play tackles the question of what happened to her, and the endless speculations and contradictions that encroach on the lives of all those living in a small, rural Ontarian town. Can we ever escape? Can we escape the gossip? The town into which we were born? Can we escape from our lives? Can we escape from ourselves? The question that the characters keep returning to is of whether Evelyn MacMillan, like Nora before her, simply got fed up being defined by her role as wife and mother and left. Do we rejoice at a woman exhibiting so much freedom? Do we cheer her and hope she is propelled toward greener pastures? But, then, what of the children? The children are the link between Gibson and Ibsen. How do we feel about the idea of a woman abandoning her children? Missing provides only ambiguities and it complicates itself with a sub-plot involving Carol Seaforth, the officer assigned to Evelyn MacMillan’s case, and her boyfriend Ian, a schoolteacher, who bends over backwards to accommodate his wife’s professional ambitions amid festering irritation and resentment. Does gender matter in selfishness? Where is the balance and how can one achieve it? Is it easier than we first assume for us to eventually become Evelyn MacMillan?

The play owes it dynamism to the performances of some of its actors. Fiona Highet is mesmerizing as Carol Seaforth, a woman so torn between her secret desires and her obligations. Andrew Gillies is equally touching as her boyfriend, Ian, as we see his language and ability to communicate disintegrate throughout the play. I found this relationship to be extremely interesting, and particularly unique at the onset on the play, and I can’t decide whether Gibson’s treatment of these characters is reinforcing a stereotype, only in reverse, or suggestive that under identical circumstances, men and women may not react all that different from one another.

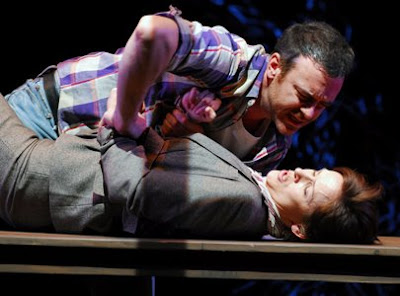

Alan Van Sprang is incredible as Trevor, Evelyn MacMillan’s mixed-up (but beautiful) husband who at times seems incapable of translating his own thoughts and emotions into anything intelligible. Van Sprang can elicit empathy, distain and pity from the audience nearly simultaneously. There are no clear-cut villains or heroes in this play. The star of the piece is undoubtedly Shauna Black, whose heart wrenching portrayal of Elaine bursts with vivacity and stubborn fortitude to forge a path for herself, when she is so obviously stuck in the mud. Black has captured Elaine’s naïve heart and inhabits every contradiction and ambiguity that the playwright has thrown at her, with pure, unique earnestness, so Elaine never feels didactic or weighed down by that which her character might “represent” or “symbolize.”

There are also some great directorial moments by David Ferry. Some of the chorus scenes are gripping, and some of the lighting choices are very powerful. I haven’t seen mimed food and drink in a professional, realist play for a very long time, and while I found it slightly off-putting, I can’t decide if it detracted from my experience or not.

At the end of the play I overheard Florence Gibson speaking to another playwright/performer who I adore, and they were discussing the choices that she and Ferry had made, which ones worked, and those that are still in development. That’s what I love about Factory Theatre, the works there are always in development. That means that they are somewhat less polished than the shows of other theatres, but we are so fortunate to have a professional theatre company so dedicated to providing opportunities for Canadian playwrights to write. Factory respects the artists’ process, and doesn’t force it. Factory Theatre tends to say yes in an industry that so often says no. I hold that in high esteem. In all, there is lots of great theatre in Missing, and although parts of it may still be raw, at its core, that proverbial slammed door still reverberates.

Missing plays at Factory Theatre until April 5, 2009. 125 Bathurst Street (at Adelaide). For tickets call 416 504-8871 or visit their website.

Evelyn MacMillan has disappeared, vanished into a fallow field one ordinary day in an unspecified year in the 1970s. Gibson’s play tackles the question of what happened to her, and the endless speculations and contradictions that encroach on the lives of all those living in a small, rural Ontarian town. Can we ever escape? Can we escape the gossip? The town into which we were born? Can we escape from our lives? Can we escape from ourselves? The question that the characters keep returning to is of whether Evelyn MacMillan, like Nora before her, simply got fed up being defined by her role as wife and mother and left. Do we rejoice at a woman exhibiting so much freedom? Do we cheer her and hope she is propelled toward greener pastures? But, then, what of the children? The children are the link between Gibson and Ibsen. How do we feel about the idea of a woman abandoning her children? Missing provides only ambiguities and it complicates itself with a sub-plot involving Carol Seaforth, the officer assigned to Evelyn MacMillan’s case, and her boyfriend Ian, a schoolteacher, who bends over backwards to accommodate his wife’s professional ambitions amid festering irritation and resentment. Does gender matter in selfishness? Where is the balance and how can one achieve it? Is it easier than we first assume for us to eventually become Evelyn MacMillan?

The play owes it dynamism to the performances of some of its actors. Fiona Highet is mesmerizing as Carol Seaforth, a woman so torn between her secret desires and her obligations. Andrew Gillies is equally touching as her boyfriend, Ian, as we see his language and ability to communicate disintegrate throughout the play. I found this relationship to be extremely interesting, and particularly unique at the onset on the play, and I can’t decide whether Gibson’s treatment of these characters is reinforcing a stereotype, only in reverse, or suggestive that under identical circumstances, men and women may not react all that different from one another.

Alan Van Sprang is incredible as Trevor, Evelyn MacMillan’s mixed-up (but beautiful) husband who at times seems incapable of translating his own thoughts and emotions into anything intelligible. Van Sprang can elicit empathy, distain and pity from the audience nearly simultaneously. There are no clear-cut villains or heroes in this play. The star of the piece is undoubtedly Shauna Black, whose heart wrenching portrayal of Elaine bursts with vivacity and stubborn fortitude to forge a path for herself, when she is so obviously stuck in the mud. Black has captured Elaine’s naïve heart and inhabits every contradiction and ambiguity that the playwright has thrown at her, with pure, unique earnestness, so Elaine never feels didactic or weighed down by that which her character might “represent” or “symbolize.”

There are also some great directorial moments by David Ferry. Some of the chorus scenes are gripping, and some of the lighting choices are very powerful. I haven’t seen mimed food and drink in a professional, realist play for a very long time, and while I found it slightly off-putting, I can’t decide if it detracted from my experience or not.

At the end of the play I overheard Florence Gibson speaking to another playwright/performer who I adore, and they were discussing the choices that she and Ferry had made, which ones worked, and those that are still in development. That’s what I love about Factory Theatre, the works there are always in development. That means that they are somewhat less polished than the shows of other theatres, but we are so fortunate to have a professional theatre company so dedicated to providing opportunities for Canadian playwrights to write. Factory respects the artists’ process, and doesn’t force it. Factory Theatre tends to say yes in an industry that so often says no. I hold that in high esteem. In all, there is lots of great theatre in Missing, and although parts of it may still be raw, at its core, that proverbial slammed door still reverberates.

Missing plays at Factory Theatre until April 5, 2009. 125 Bathurst Street (at Adelaide). For tickets call 416 504-8871 or visit their website.